Have you ever prayed before an altar that was produced by a 3D printer? Hallelujah, now it’s finally possible in the parish church of St. Laurentius in the Bavarian village of Altmühldorf.

Gazing down the nave, your eye is immediately drawn to a graceful grid construction with a skeletal appearance. The lower part has a somewhat more densely meshed feel to it, but it is delicate in the middle. And at the very top, it has an almost airy quality. With a width of two-and-a-half metres and a height of eight metres, this towering sculpture reaches up to the heavens, both literally and figuratively.

Yes, this masterpiece is in fact the church altar, yet it is also the product of a remarkable earthly invention: a 3D printer was the technological creator that gave life to this divine work of art!

A complex renovation

But let’s start at the beginning. The original Late Gothic parish church of St. Laurentius underwent several alterations over the years. Unfortunately, the modifications made from the baroque period up until the 1960s had a fairly negative impact on the overall appearance of the church.

This has now been corrected during carefully considered general restoration. All work has been in keeping with the guidelines of the Venice Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, which states that individual stylistic periods are to remain visible following renovations of historical churches that have been altered over time. The idea is that all architectural amendments should, ideally speaking, nevertheless bear some relationship to the present day and age. Which is where a 3D printer comes into the picture…

It was decided that the back part of the altar, known as the “retable” – from the Latin retabulum – was to become the centrepiece of a new design for the church interior. To make this creation truly unique, the renowned Munich-based artist duo Corbinian Böhm and Michael Gruber were commissioned with the work.

Exterior view of St. Laurentius church: a sculpture in front of the church arouses curiosity about the altar inside.

From a 3D printer

And these two creative spirits have come up with something spectacular:

For centuries, churches have served as repositories for our cultural heritage. We wanted to add something that stems from the present-day era and at the same time enriches the church interior, which is characterized by diverse architectural styles,

Böhm and Gruber said as they described their surprising idea of creating a sculpture together with architect Oliver Tessin, who specializes in 3D designs.

It’s a concept that, in their opinion, does not run counter to the architectural heritage, neither in terms of its unconventional design nor its methods of creation. On the contrary:

I saw this project as an exciting opportunity to apply my research on complex lightweight structures to precisely this area. After all, they are based on the same philosophy and logic as the Gothic architecture of the parish church of St. Laurentius. Back in the day, Gothic architects also used the forms found in nature. Pointed arches and ribbed vaults are, after all, construction and design elements derived from nature,

adds Tessin.

An alternative to using a hammer

Tessin sees computer-based design and additive manufacturing solutions as a modern alternative to working with a hammer and chisel. These new tools make it possible to design and build extremely complex structures and thus add a new twist to the Gothic approach to architecture and design. Instead of merely copying the old styles, as in 19th century historicism, this new technology paves the way for new developments. Another groundbreaking advance is the development of new super materials like graphene.

But creating this impressive sculpture was no easy task, even for the 3D printing experts at the FIT Additive Manufacturing Group.

New manufacturing processes

There were considerable technical challenges for which there was no standard procedure,

says Bruno Knychalla, Head of FIT’s Large Format Division.

For instance, the sheer dimensions of the sculpture were daunting. Objects of this size are still a rarity in additive manufacturing.

Even though today’s printers can handle increasingly larger jobs, the technology is still a long way from being able to produce something like this in one piece.

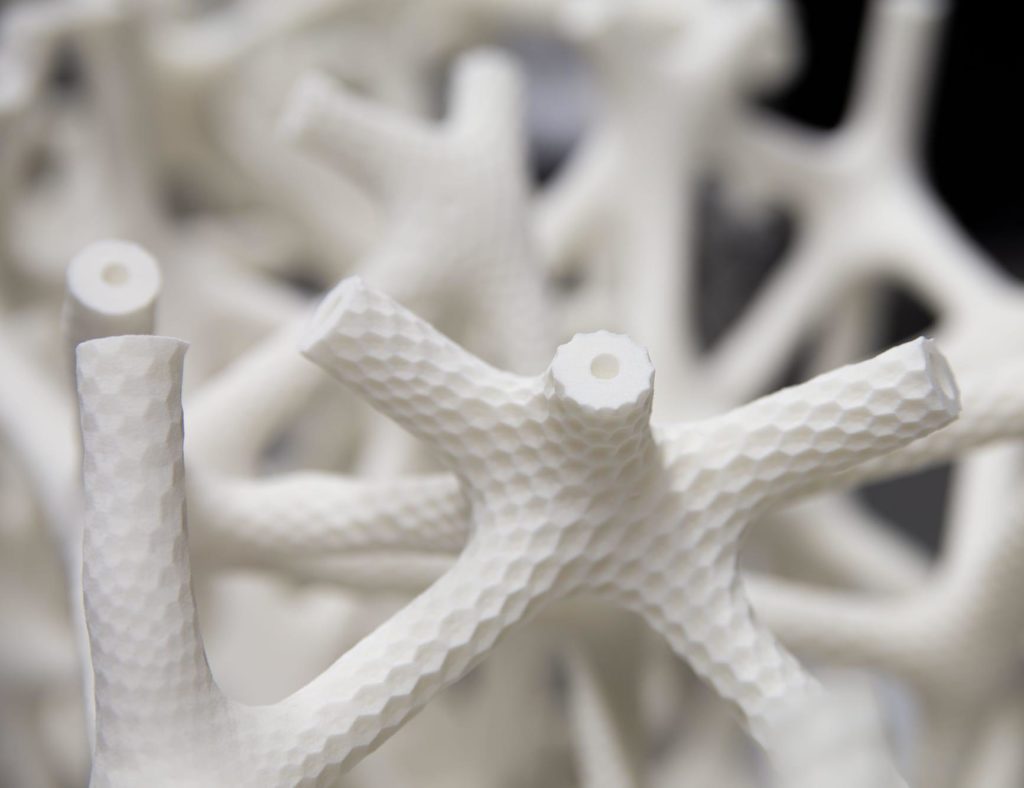

The problem was solved by breaking down the digital construction plan into a total of 60 individual pieces measuring 68 x 55 x 38 cm, which were printed separately from white polyamide plastic and later assembled. This required extreme precision and a high degree of craftsmanship.

After all, even the slightest deformation in the intricate web of connections – there were 2,000 of them – would not only have been highly visible and detracted from the overall effect, but could have also jeopardized the stability of the construction, which was precisely balanced with the aid of computer technology.

Aluminium turns to gold

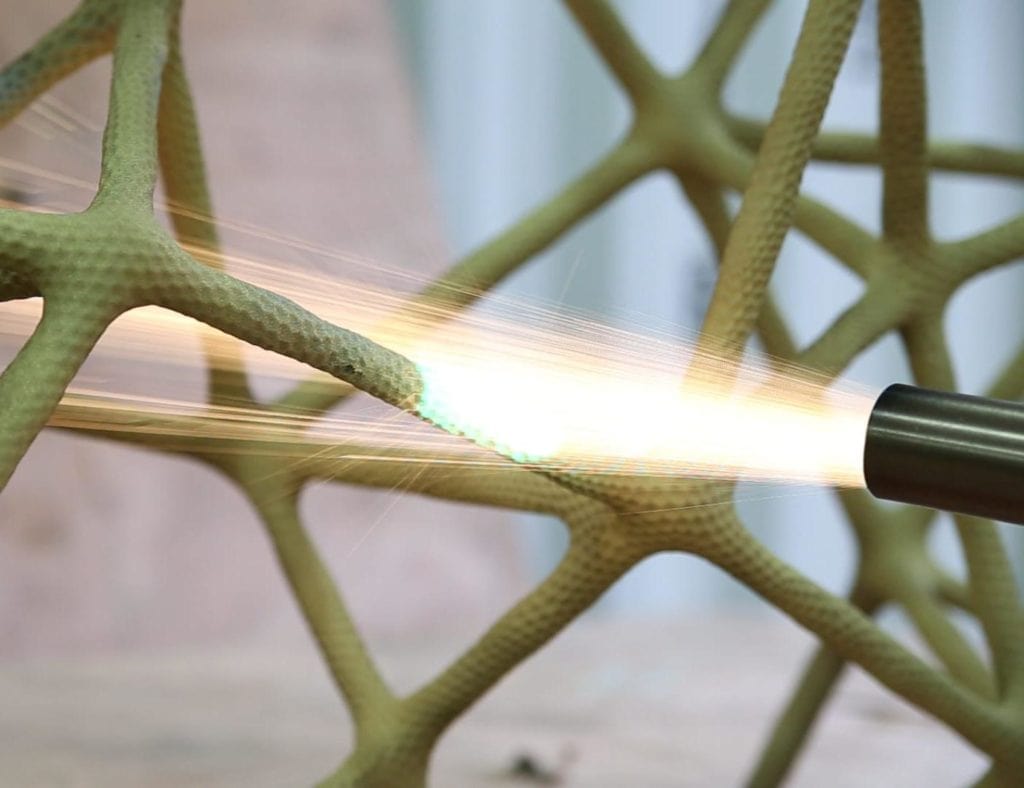

The colour finishing of the retable also required new approaches. Gold leaf was ruled out simply because it was too expensive. But there were also some very practical reasons for this decision: the coating had to meet demands that went far beyond the desire for a rich golden sheen.

Above all, it must ensure the long-term stability of the object because the polyamide ages over time. Furthermore, the surface should be smooth despite its structuring to provide a soft shimmer and play of light, but at the same time have a certain degree of resistance to oxidation and environmental influences, such as soiling from dust or soot,

explains Knychalla.

FIT engineers developed a special thermal spraying process to apply several fine layers of aluminium and a bronze-aluminium alloy to the white polyamide. The shiny golden finish was achieved with a metallic paint.

The Church is opening up

Times are changing, and so is the Church. It’s now more open up to the benefits of modern technology, at least in the areas of architecture and design, and this is reflected in other projects as well. For instance, the team that is working to complete Antoni Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia Basilica in Barcelona has been using CAD software and 3D printers since 2001, instead of conventional handmade models, to achieve much quicker results and with far greater detail.

The completed altar in all its glory.

3D models were also printed for the renovation of the Freiburg Cathedral, which was completed in 2018. The models allowed for a more effective evaluation of the computer-generated designs.

In 2014, the Pietà at the All Saints’ Church in Erfurt, which dates back to 1390, was replaced by an exact and weatherproof plastic copy made with a 3D printer. And since 2018, the black helmets worn by members of the Swiss Guard in the Vatican while on duty have no longer been made by a blacksmith, but by a company that specializes in additive manufacturing.

Compared to conventional models made of steel, the plastic replicas are not only cheaper, but also significantly more comfortable due to their lightweight design and integrated ventilation slots.

From a designer’s perspective, this makes 3D printing technology something akin to the Holy Grail of modern methods of construction. And in view of this stunning altar, the only thing to add to that is: amen.

Text: Britta Biron

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

Photos: Andreas Heddergott; Elisabeth Bauer; Lisa Kirk; Elisabeth Bauer